The Farmington Enslaved

Are you a descendant or in possession of additional historic information about the people of Farmington? We would love to hear from you. Let’s bring history to light!

Becky and her Children

Becky – 23

Fanny – 13

Tamar – 7

Martin – 5Hannah – 3

The only information we can document about Becky and her children appears in John Speed’s probate records. We know their names and approximate ages in 1841 and that Speed gave Becky and her children to his daughter, Susan Speed Davis, before he died. Although we cannot verify exactly when Becky and her children left Farmington, it was, likely, when Susan married Benjamin Davis. The Speed and Fry families, like many in Kentucky, regularly distributed enslaved people when their children married. If this is what happened, it is likely Becky was given to Susan at a young age and trained to be her personal enslaved woman. Customarily, children born to Becky would be transferred to Susan’s husband. Becky was approximately ten years old when Fanny was born.

To date, we have not discovered any additional information that tells us about Becky, Fanny, Tamar, Martin, or Hannah. We do not know if this is Becky’s entire family, or if more children were born during the six-year gap between Fanny and Tamar. We do not know if they stayed with Davis until emancipation, if they married and had children, or when they died. We are working to discover more information about all the people from Farmington.

Edwin George Jackson Newton Jacob Joseph Rowen James

Edwin 14

George 14

Jackson 11

Newton 10

Jacob 10

Joseph 10

Rowan 10

James 10

The only facts we know about the children listed here are their names, ages, and assigned values listed on John Speed’s 1841 probate inventory. There are 36 males listed on the probate inventory. Males fifteen and older are categorized as “men” while the eight listed as “boys” were ten to fourteen years old. The truth for each of these children is that we do not know who their mothers or fathers were. We do not know if they were born at Farmington or if they were purchased from somewhere else.

The assigned values of these children tell us most were old enough and big enough to start working in the hemp fields. The assigned value of ten-year-old James indicates he may have still been too small to work in the hemp fields while fourteen-year-old Edwin was probably already learning to extract fiber with a hemp brake, a very labor-intensive part of the process. George, at fourteen, had some kind of issue that reduced his assigned value. Although we can speculate on his issue no documentation has surfaced. George might be small, he might have a physical condition that lessened his productivity, he might have been injured at some point. These children were all learning to farm the crops grown at Farmington. They have not been mentioned in any other letters or documents discovered so far.

At the end of the Civil War, Edwin & George would have been 38 years old, Jackson 35, and the rest of these young men would have been 34 years old. We do not know if any of these young men married, had children or lived to see freedom. We are working to discover the facts about all the people of Farmington.

Name Age Assigned value

Edwin 14 $700

George 14 $300

Jackson 11 $450

Newton 10 $450

Jacob 10 $450

Joseph 10 $450

Rowan 10 $450

James 10 $200

Sarah also called Sary

Celia

Anderson

These three people’s names appear in the list of individuals on John Speed’s probate inventory. Sarah, or Sary, was 21 years old. We do not know her parents, where she was born, or how many children she had. As administrator of his father’s estate, James Speed listed her in the count of people then later said, referring to the listing, that “Sary died shortly after.”

We do not know the names of five-month-old Celia’s mother or father, only that, according to James Speed, “Celia, an infant, [died] a few weeks since.”

Two-year-old Anderson’s story is an anomaly. We do not know the names of Anderson’s mother or father. The little boy’s name appears on John Speed’s probate inventory but there is no account of who received him. We cannot tell, from the existing record, where he went after distribution of the estate or if he died before the settlement. We hope to learn Anderson’s story as we learn more about all the people of Farmington.

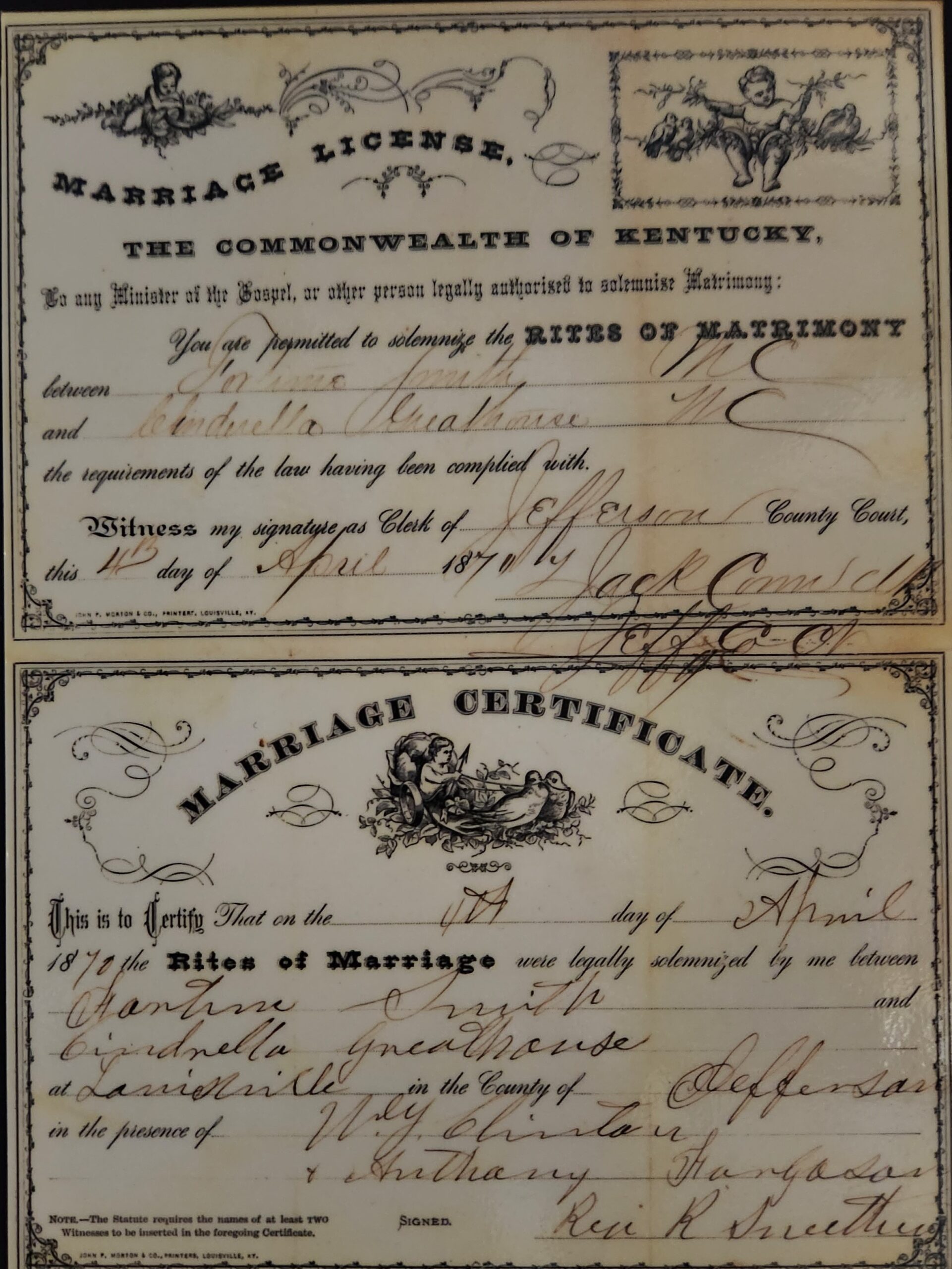

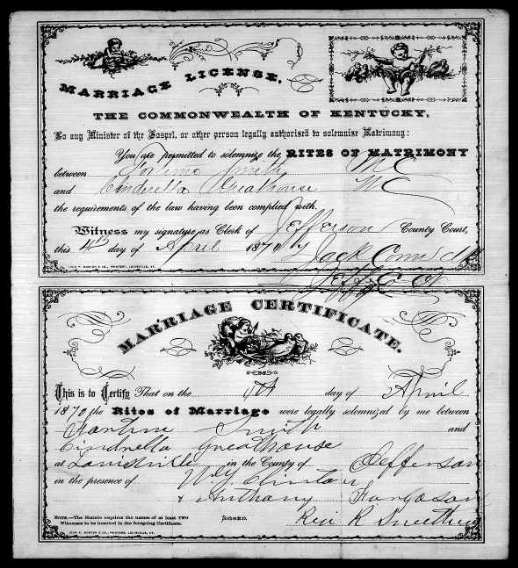

Fortune Smith

Cinderella Greathouse Smith

Fortune and Sinderella were listed on John Speed’s 1840 probate inventory. Fortune, age 17, was assigned a value of $800 dollars, one of several young men given that designation. It tells us Fortune was considered one of the most vital hemp workers at Farmington, a strong young man capable of harvesting, breaking, and processing the fiber crop. Sinderella, as the name was spelled on the inventory, was four years old. Joshua Speed inherited SInderella and his brother Philip received Fortune. Neither Sinderella nor Fortune are mentioned in any additional Farmington records that have surfaced to date. After the Civil War, Sinderella is spelled the traditional way.

Fortune was 42 years old and Cinderella, 29 when the ratification of the 13th amendment freed them. Although they were “married during slave times,” Fortune and Cinderella Greathouse Smith were legally married on April 4, 1870. Census information tells us that Fortune was a farm laborer and, later, a drayman delivering beer. Cinderella was a housewife. There is no record available to tell us if they had children when they were enslaved, and no children appear on censuses with them after the Civil War.

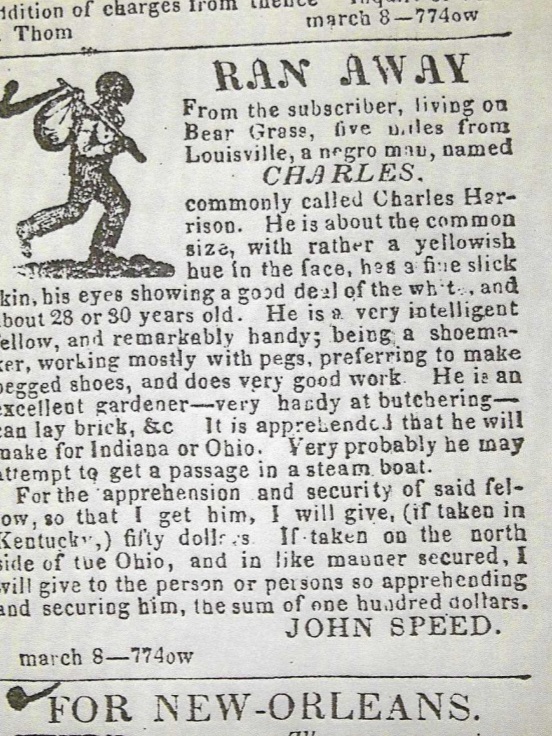

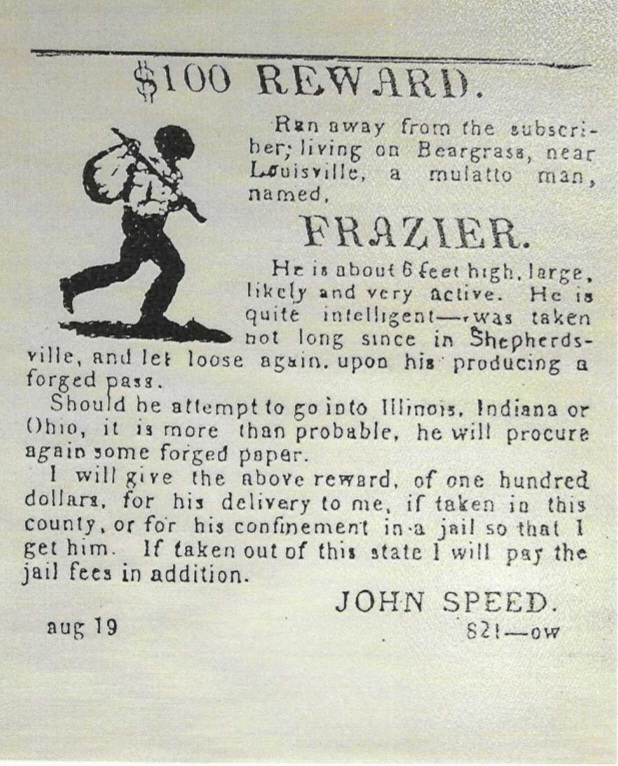

Frazier and Charles Harrison

In 1826 John Speed placed ads in the Louisville Advertiser for the capture of two skilled men, Charles and Frazier, who escaped enslavement at Farmington. These ads reveal more personal information about two of the men enslaved at Farmington than any other primary document to date. Frazier and Charles Harrison are described as highly intelligent, both are expected to attempt to get to a neighboring, free state.

Frazier is racially mixed, about six feet tall, attractive, and energetic. He is also literate and able to forge the passes necessary in Kentucky for the enslaved to travel unimpeded. Because special skills are not listed, Frazier was, despite his intellect, an agricultural worker at Farmington.

Although Charles Harrison probably worked in the hemp fields, he was also a highly skilled shoemaker, butcher, and gardener.

We do not know, however, where either man was born or how long Speed had owned them. We do not know their parents’ names, if they ever married, or had children.

We do not know if they successfully self-emancipated or if they were returned to Farmington. Their names are not listed on the 1840 probate inventory or included in any other documents found thus far.

Grace Albert Mary Lucy

Grace – 12

Albert – 2

Mary – 14

Lucy – 17

Grace, Mary, and Lucy are the youngest females listed as “women” on John Speed’s probate inventory. Females who gave birth were classified as “women” regardless of their age. Eliza Speed inherited twelve-year-old Grace and two-year-old Albert. Because Grace is the only woman Eliza inherited, and Albert the only small child, it is likely they are mother and son. If they are not, Grace, the only female transferred in this group, would still become Albert’s de facto mother. Tax records indicate that Eliza no longer owned slaves by 1854 but we do not know who purchased Grace and Albert, if they were sold together, or if they remained in the Louisville area.

Mary, age fourteen, is inherited by future Attorney General James Speed. Mary, classified as a “woman” is transferred without a child, a situation that could mean a number of different things. Mary’s child was, most likely, dead. However, Mary’s child could have been sold or could have gone to a different Speed family member than its mother. We cannot tell for certain with the information we have so far. James Speed emancipated the people he enslaved in the early 1850s. If Mary and Albert remained with James until then, they would have been free. We do not know if Mary and Albert were two of the people James emancipated.

Lucy, age seventeen provides an anomaly on the inventory. There is no record of who inherited Lucy, we do not know if she was given with children or alone. She could have died, although James Speed noted dead enslaved people for the record. We have not uncovered any additional information about Lucy. We are looking for information to help us tell more about Lucy, Mary, Albert, and Grace.

Johnston

Jacob

Oz

John Speed’s 1840 probate inventory tells very little about Johnston, Jacob, and Oz other than their names, ages, and the value assigned by the estate administrator. Oz, at 55, was the youngest of the three with an assigned value of $250. Jacob and Johnston, both 60, were assigned values of $200.

These are the older men at Farmington. They are the experienced hemp hands, but their physical prowess no longer matches that of the younger men, some of whom were assigned a value of $800. Despite their ages, Johnston, Jacob, and Oz still operated the backbreaking hemp brakes that separated the fiber from the stems. They would have expertise in all the field crops grown at Farmington including hemp, apples, and corn. These skilled farmers likely shared their expertise training the younger men working the plantation fields. These facts, however, tell us nothing about the personal lives of Johnston, Jacob, and Oz.

Johnston, was one of the people given to John Speed by Joshua Fry. We cannot determine, however, if he is related to Phillis, Morocco, and their mother. He was given to Speed at approximately age 19 and lived most of his life at Farmington. We do not know who his parents are, if he married, or if he had children.

Farmington has not discovered any additional information about Jacob or Oz. We do not know their parents’ names or where they were born. We don’t know how old they were when they came to Farmington. We do not know if they ever married, had children, or when they died. No additional records or letters have been uncovered that mention these men.

Morocco – 44

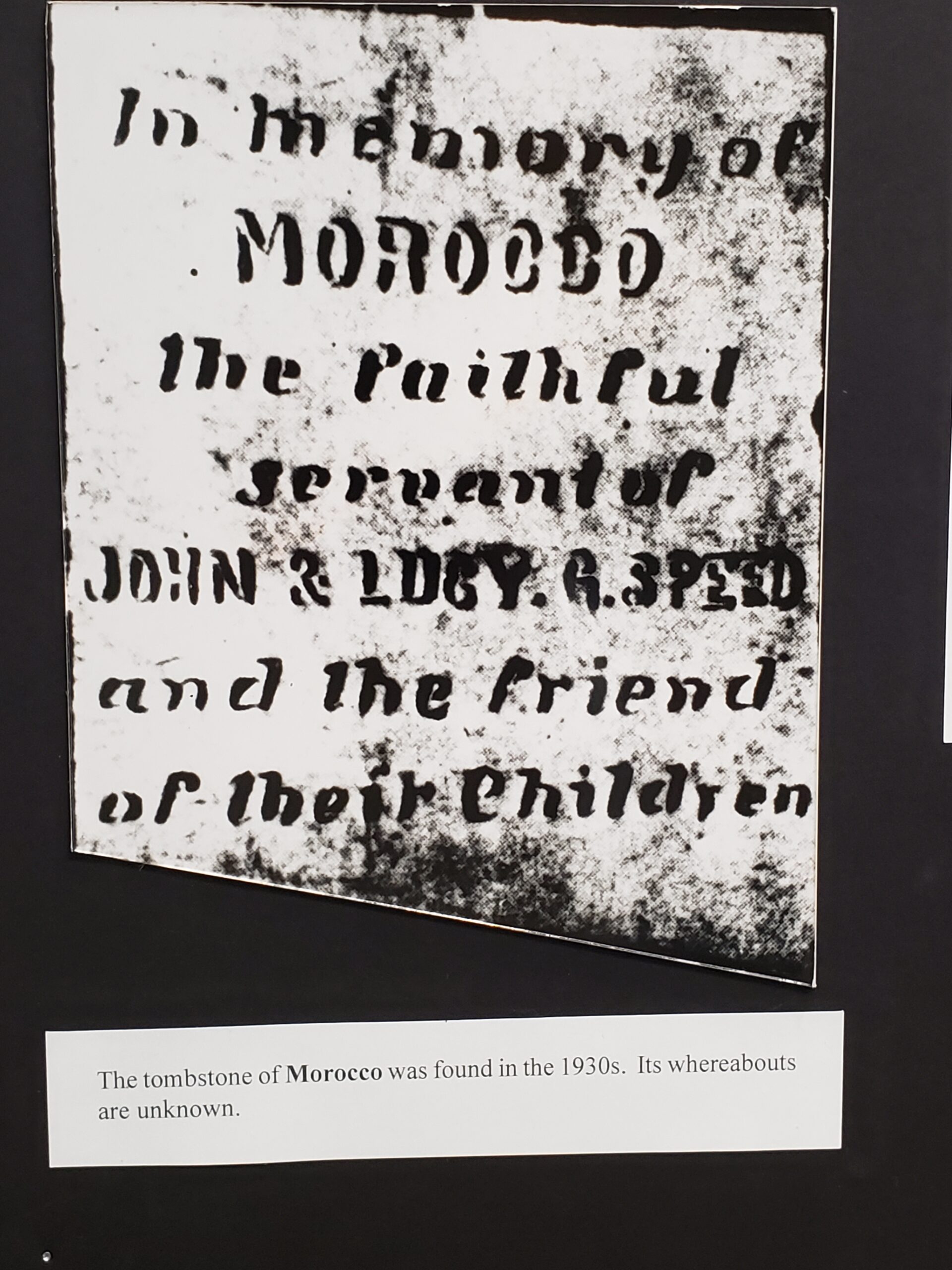

“In memory of Morocco the Faithful Servant of John and Lucy G. Speed and the friend of their Children”

Morocco is the only person enslaved at Farmington for whom a tombstone has been located. Uncovered by a farmer plowing a field in the 1930s, Morocco’s tombstone remarks solely on his service to the Speed family. His life, however, was far more complex than this simple tombstone indicates. In 1800, when Morocco was about four years old, he, along with his sister Phillis, and their unnamed mother were given as wedding gifts from Joshua Fry to his new son-in-law, John Speed. Together, they formed the nucleus of a family enslaved by the Speeds for at least four generations.

Morocco grew to adulthood and was the primary coachman at Farmington. He was frequently sent to deliver letters, sell products at market, and chaperone the Speed children. He had a great deal of familiarity with the Speed family and was respected by the enslaved. According to Speed friend, Unitarian minister Samuel Osgood, “The coachman was a thorough-going mystic, a believer in visions and trances, which he interpreted to auditors, who listened with open ears and distended eyes. He was a preacher, as he and his admirers thought, of heaven’s own ordaining; and, although occasionally somewhat given to excessive potations, his hearers, with an acuteness equal to that of many pious white people under similar circumstances, carefully distinguished between the infirmities of the man and the inspirations of the saint.”

John Speed offered to free Morocco if he would move to Liberia. Morocco refused to leave the United States and so remained enslaved at Farmington with his family. Morocco said he would not have children who were enslaved and, to date, there is no evidence of anyone descended from Morocco. In 1840, Morocco is listed as 44 years old with a $600 value indicating he is still working in the hemp fields. No record has surfaced that tells us when Morocco died.

Mother of Morocco and Phillis

We do not know Her name

We know some of Her story. She and Her children, Morocco and Phillis, were given to John Speed by his new father-in-law, but we do not know Her name. She was, likely, Lucy Speed’s personal slave, and probably lived at Farmington from young adulthood until she died, but we do not know for certain. We know She was Matriarch of a family enslaved for at least four generations at Farmington, but we do not know Her name.

She could be the enslaved woman, Peggy, given to Lucy Speed in her husband’s first will. Or, She could be 68 year old Nannie, listed on Speed’s probate inventory. She might be someone else whose name never appears. We are working to find information on as many people from Farmington as possible, but we don’t know Her name.

She had at least one son, Morocco, and we know She generated a strong matrilineal line that included Phillis Thurston, Jinnie, Diana, and Dinnie Thompson, but we do not know how many children she had, if she was allowed to marry, or her husband’s name. We don’t know Her parents’ names, when She was born, or when She died. We will share the courage of Her descendents in future posts.

Rose-Harrod-Sally

“The plan took about the currents (sic) – Morocco and Rose sold all at fourpenneys a qt.” is the one bit of information we have about Rose, who was 20 when John Speed wrote this letter to his wife, Lucy.

In 1840, Rose’s assigned value the highest of all women listed while Sally, 33, was given the second highest value. Rose and Sally were highly skilled and either woman could have been a cook or seamstress at Farmington. Lucy Speed inherited Rose, and Speed daughter Lucy Breckenridge inherited Sally when the estate settled. Both women eventually would have moved into Louisville with their new owners.

In 1845 Rose, her son Harrod who was born after John Speed died, and Sally were freed. We do not know the identity of Harrod’s father. Because we do not have a last name for any of the three, we are not able to find them in a census. In an 1863 Freedmen’s Bureau interview James Speed said, “My sister liberated all the slaves she had, and they are in Canada and Michigan, and write to her that they are doing very well.” Because Lucy Breckenridge is the only sister we can document freeing people it is likely James is referring to Sally, Rose, and Harrod. We know that the people James referred to became literate as soon as they were free. Farmington can now look for more descendants of the enslaved in Michigan and Canada in hopes of finding more connections to this site.

Peay enslaved

Mary

Patsy

Louisa

Johnston

Alfred

Aaron

We know so very little about Mary, Patsy, Louisa, Johnston, Alfred, and Aaron. Their names appear in one document that has surfaced so far, Austin Peay’s will. We do not know their ages, their parents or even the jobs they performed at Farmington.

Austin Peay purchased Farmington from his mother-in-law, Lucy Speed, in 1843. In March 1840, John Speed transferred an unknown number of people to Peay as part of his wife Peachy’s inheritance, two days before he died. Some of the people listed here may be the people given to Peay in 1840. Austin’s wife, Peachy, inherited these people from her husband in 1849 but no additional information has surfaced yet to tell us the lives and stories of these individuals.

Phillis

Phillis was Morocco’s younger sister, given to John Speed by his new father-in-law, Joshua Fry, when she was about three years old. Phillis grew to adulthood and lived almost her entire life at Farmington where her mother was also enslaved. Although we don’t know her specific skill set or daily jobs, we know she is the second generation of a family enslaved by the Speeds for at least four generations. Although we don’t know how many children were born to Phillis at Farmington, we know she was Diana’s mother and the grandmother of Dinnie, Henry, and Bob, people you will learn about in later columns.

Phillis was listed on John Speed’s 1840 probate inventory. She was given a value of $300, half that of younger women. Because the babies produced by enslaved women were in high demand throughout the southern United States, a woman’s value rose or fell according to her ability to bear children. Phillis’ diminished monetary value tells us she was no longer capable of doing so.

Robin, sometimes spelled Robbin

Robin was born in approximately 1799. We do not know his mother or father’s name, we do not know where he was born, or when he came to Farmington.

We can unravel a bit of Robin’s story through a Speed family letter. In 1835, Robin traveled to Lexington with Speed children Smith and Lucy. Smith had injured his leg severely and was sent to a physician, Dr. Dudley, to help with his recovery. Morocco also accompanied the group to Lexington, but Robin stayed at Dr. Dudley’s with the two Speed children. Two 1835 letters contain messages from most of the Speed family members to their siblings. These letters contain tidbits of information about the people enslaved at Farmington.

We learn of a possible connection between Robin and Jinnie, Phillis and Morocco’s sister who lived at Oxmoor, from Mary Speed who asks Smith to “Tell Robbin Jinny did not come yesterday, but she is well, I expect the rain prevented her, but she sent a dress to Sister Philis (sic) for little Ellen Clendenen.”

Mary writes, “I miss Robbin very much I want to have the chimney burned, and no body can do it as well as Robbin, and whenever I want a backlog put on in the drawing room, the first thing I think of is Robbin…”

She also tells us the reason Robin was sent with the children, “…I will dub him with the honorable title of Dr. Robbin after he graduates under Dr. Dudley, so after this it will be Dr. Robbin a graduate of Dr. Dudley of Lexington.”

Robin was sent to learn how to care for Speed’s injury when the children returned to Farmington. Early records indicate doctors visited Farmington occasionally and treated the enslaved as well as the Speed family. Giving a man like Robin medical training would be a tremendous asset on a site like Farmington. When Speed died in 1840 Robin was assigned a value of $600, double that of most men close to his age. This indicates that he is still in good physical condition and he probably still worked in the hemp fields. But the elevated value comparable to other men indicates Robin has special training and skills, perhaps some of those were learned from Dr. Dudley.

Lucy Speed inherited Robin when her husband died, so he stayed probably remained at Farmington. We do not know if Robin married, had children, or when he died.

Rose-Harrod-Sally

“The plan took about the currents (sic) – Morocco and Rose sold all at fourpenneys a qt.” is the one bit of information we have about Rose, who was 20 when John Speed wrote this letter to his wife, Lucy.

In 1840, Rose’s assigned value the highest of all women listed while Sally, 33, was given the second highest value. Rose and Sally were highly skilled and either woman could have been a cook or seamstress at Farmington. Lucy Speed inherited Rose, and Speed daughter Lucy Breckenridge inherited Sally when the estate settled. Both women eventually would have moved into Louisville with their new owners.

In 1845 Rose, her son Harrod who was born after John Speed died, and Sally were freed. We do not know the identity of Harrod’s father. Because we do not have a last name for any of the three, we are not able to find them in a census. In an 1863 Freedmen’s Bureau interview James Speed said, “My sister liberated all the slaves she had, and they are in Canada and Michigan, and write to her that they are doing very well.” Because Lucy Breckenridge is the only sister we can document freeing people it is likely James is referring to Sally, Rose, and Harrod. We know that the people James referred to became literate as soon as they were free. Farmington can now look for more descendants of the enslaved in Michigan and Canada in hopes of finding more connections to this site.

Abram and Rosanna Hays

The descendants of Abram and Rosanna Hays have shared an incredible amount of information about their ancestors with Farmington. Abram Hays was born August 26, 1823, enslaved in the Maryland/Virginia area. We do not know who his parents were. Hays family tradition tells us John Speed brought Abram to Farmington as a young boy.

Rosanna was born in May of 1825 in Louisville, Kentucky. She may have been born at Farmington, but we cannot prove this. Abram died June 6, 1904 and Martha died in the early 1900s, but her exact death date was not recorded. They are the only two people enslaved at Farmington for who we have birth and death dates.

Abram and Rosanna were, probably, two of the people John Speed gave his daughter, Peachy Peay, before he died. This act was referenced in a March 27, 1840 codicil to his will but it does not give names. Abram and Rosanna are both listed on Austin Peay’s 1848 probate inventory. Hays family tradition is that Abram was inherited by Peay’s daughter, Eliza Ward.

Abram and Rosanna Hays were married at Farmington in 1848. Their children were Louis, Sally, Mary Jane, Louisa, and Charlotte, who did not survive to adulthood. The family does not believe the Hays had any children that were sold before the end of slavery. After slavery, the Hays family revealed that Eliza Peay Ward provided Abram and Rosanna a house on Goss Avenue, horses and farming equipment. Peachy Peay ensured their lifetime residence in the house in her will. Abram and Rosanna are the only people enslaved by the Speed family we know of that received this type of support. We hope more information will uncover the structure of the relationship between the Hays and the Peays.

After slavery, the descendants of Abram and Rosanna Hays sought education. They became teachers, doctors, farmers, lawyers, plumbers, and carpenters. Today, they live across the nation but still maintain an important presence in Louisville. Hays Kennedy, for whom a park in the Louisville Metro Park system is named, is the descendant of Abram and Rosanna Hays.

Special thanks to Frances V. Halsell Gilliam and Danyel Edwards for sharing the history of their ancestors with Farmington.

David and Martha Spencer

Descendants of David and Marth Spencer contacted Farmington in the 1990s and have been instrumental in helping us discover the stories of their ancestors ever since. Spencer family tradition says that David, born approximately 1825, was enslaved by John Speed before he was at Farmington with Austin Peay. It is likely he was one of the unnamed people transferred as Peachy Peay’s inheritance in a codicil to John Speed’s will. Martha, born approximately 1845, was too young to have been owned by John Speed. She might have been born at Farmington but we cannot document this yet. David might have also been born at Farmington but we do not know for certain.

Spencer family oral tradition indicates that Martha was a cook at Farmington, a highly skilled position that gave enslaved women status. Many of her descendants are also talented cooks and say recipes were passed down through her daughters and granddaughters. David was likely an agricultural worker while enslaved at Farmington. After the Civil War, when the Spencers were freed by the 13th amendment and moved to nearby Newburg, David became a bricklayer. A Spencer family tradition is a story about the secret ingredient David used to make his mortar exceptionally strong.

David and Martha Spencer raised seven children to adulthood after the Civil War. We do not know if they had additional children who were sold prior to the end of slavery. After the Civil War, David’s name appears on the census and in legal documents and on the marriage records of his children. Martha’s name appears with David’s on death records. The records indicate her maiden name was Smith. Although both David and Martha lived to be very old, the year either died is not documented.

In 2003, a family reunion brought descendants of David and Martha Spencer together at Farmington. Their numerous descendants live across the United States. They are teachers, construction workers, doctors, politicians, military personnel, almost every occupation available. In 2018, the only African American mayor of a Jefferson County incorporated city was Glenn Sea, a Spencer descendant. Farmington is grateful to the descendants of David and Martha Spencer for sharing their ancestor’s information and stories.

Special thanks for this information go to researcher and Farmington Board member Cassandra Sea, whose husband and children are descended from David and Martha Spencer and to Miss Anna Merritt, also descended from the Spencers.

Toddlers and Boys

Thos Adams – 2

Harrison – 5

Charles – 3

Jonathon – 5

Harrison – 5

Minor – 4

Right now, the only information we have about these toddlers and little boys is their names and ages in 1840. We do not know for certain who their mothers and fathers were. They were probably born at Farmington. When John Speed died, there were 17 children younger than age 10 enslaved at Farmington. Because Eliza Speed inherited two-year-old Thos Adams and Sally, they could be mother and son but we cannot document the information.

Although we do not have any additional information about these children, they would all have been in their twenties during the Civil War. If they survived into adulthood it is likely they were freed after the ratification of the 13th amendment. We have not been able to identify any of these children as adults.

CONTACT FARMINGTON HISTORIC HOME

TOUR TIMES

Tuesday - Friday

10:30am 12:00pm 2pm

Saturday

11:00am 12:00pm 1pm

School & other group tours please contact the office to schedule.