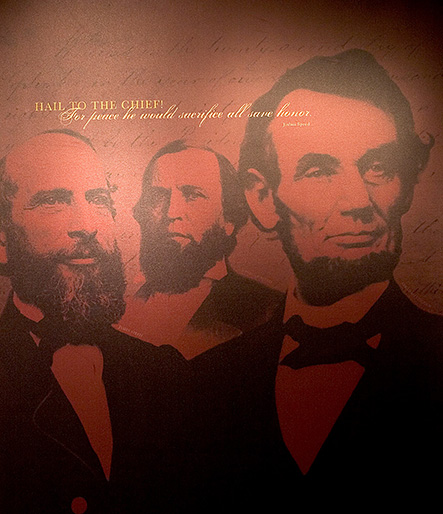

Abraham Lincoln and Farmington

In August of 1841, Abraham Lincoln traveled from Illinois to Louisville, Kentucky, to visit Joshua Speed and his family at Farmington.

Abraham Lincoln and Farmington

ABRAHAM LINCOLN’S return to the Bluegrass State in 1841 introduced him to the privilege of antebellum plantation living. The friendship that brought him back to Kentucky would later sharpen the views and inform the policies of his presidency. His host, Joshua Speed, was his closest friend—and a slave owner. Their friendship endured, however; despite political differences that had divided other friends and families, as well as the nation.

ABRAHAM LINCOLN’S return to the Bluegrass State in 1841 introduced him to the privilege of antebellum plantation living. The friendship that brought him back to Kentucky would later sharpen the views and inform the policies of his presidency. His host, Joshua Speed, was his closest friend—and a slave owner. Their friendship endured, however; despite political differences that had divided other friends and families, as well as the nation.

Joshua Speed first encountered Abraham Lincoln when the latter was running for re-election to the Illinois state legislature. According to Speed, the twenty-seven-year-old Whig politician was one of the best orators he had ever heard. Thus, when Lincoln arrived in Springfield a year later, on a borrowed horse, to begin a career as junior partner to attorney John Todd Stuart, they were not complete strangers.

Once in Springfield, Lincoln came to the Bell and Company store to purchase a mattress, pillows, and linens for his bed. Lincoln thought Speed’s calculation of seventeen dollars for the lot was a fair price, but he was unsure he would be able to repay that amount. Moved by the young man’s melancholy face, Speed suggested that Lincoln share his own quarters above the store. Speed recounted:

“He took his saddle-bags on his arm, went upstairs, set them down on the floor, and came down with the most changed countenance. Beaming with pleasure, he exclaimed, “Well, Speed, I am moved!”

The two men shared quarters for four years and developed a very close friendship. At times, other young men lived above the store with them, including Billy Herndon, Lincoln’s future law partner, and Charles Hurst, a clerk in the store. The group formed a social circle of politically active young men who gathered at Bell and Company in the evenings, drawn there, according to Speed, because of the charismatic Lincoln. Some of these men, including Stephen A. Douglas, John Hardin and Edward Baker, later became prominent in state and national politics.

Despite Lincoln’s lack of social Status, Speed helped secure his friend’s acceptance into elite Springfield homes, including that of Ninian and Elizabeth Edwards. These gatherings typically included socially prominent, eligible women, including Elizabeth’s attractive younger sister, Mary Todd. Lincoln courted Mary Todd for about a year before proposing marriage. He regretted his proposal almost immediately,

however; the practical Lincoln doubted his ability to sup port Mary, the daughter of a successful banker from Lexington, Kentucky. Realizing that he could not provide the luxurious surroundings of her youth on the income from his legal practice and the salary he earned as a state legislator, he broke off their engagement.

Lincoln was carrying a heavy legal caseload in the Sangamon County circuit court while he pursued Mary Todd. He was also the floor leader in the Illinois legislature for the Whig political party. This was during a time when the party’s platform of internal improvements to roads and canals had thrown the state into a financial crisis, and the turmoil and stress caused by these pressures pushed Lincoln into a deep depression. According to Speed, “In the winter of 1841 a gloom came over him until his friends were alarmed for his life.” In addition, Speed was getting ready to return to Louisville, and the impending absence of his close friend did not help Lincoln’s emotional state.

After the March 30, 1840 death of John Speed, Joshua’s father, the young merchant traveled home briefly to be with his mother, Lucy Speed, and the rest of his family. He then returned briefly to Illinois and, in the winter of 1841, sold his shares in Bell and Company and prepared to return to Louisville. Before leaving Springfield, Speed invited Lincoln to accompany him to Farmington.

Lincoln arrived at the bustling Louisville wharf in early Au gust, hub of the fifteenth largest city in the United States. Lincoln probably traveled the six miles from Louisville to Farmington via the Bardstown Turnpike, a rural toll road that connected farms and plantations to Louisville’s markets. Enslaved Blacks from Farmington built part of the Turnpike. In 1811 the Jefferson circuit court appointed John Speed to supervise the extension of the road beyond his property and directed him to provide the necessary labor.

At Farmington, Lincoln entered a world beyond his experience. The plantation was a large, agricultural enterprise where a work force of almost seventy enslaved Blacks and two free Blacks comprised the racial majority of the community that provided a privileged lifestyle for the Speed family. Although John Speed claimed to be an emancipationist, he never freed anyone he enslaved. Speed’s probate inventory lists fifty-seven men, women and children held at Farmington with a codicil telling that other people had already been given to his children. His will divided these individuals (as property) between his wife, Lucy, and his eleven surviving children, a practice that was typical in Kentucky and throughout the slaveholding South. Many of the people enslaved by Speed were probably still on the property when Lincoln visited.

Lincoln arrived at Farmington about six weeks before the harvest of many primary and secondary crops—one of the busier times of the year. An eighty-acre field of hemp, along with corn, oats, and other field crops, surrounded the built environment. Apples, peaches, and pears ripened in their or chards while kitchen gardens produced a variety of fruits and vegetables. Horses, cattle, and sheep grazed in the fields; poultry and swine foraged in the yards. Lincoln observed a successful Kentucky hemp operation. In a good year, seed planted in the spring grew into fifteen-foot stalks by fall. Over the winter months, slaves extracted fiber from the dried stalks and later wove it into twine and rough bag ging for use in southern cotton fields. Structures specifically designed to support hemp production included a ropewalk, a hemp barn and a hemp-weaving house.

According to Joshua’s older brother, James, enslaved women at Farmington rarely worked in the fields. Their work was, however, equally physically demanding. They planted, weed ed and harvested kitchen gardens, prepared and preserved food, cared for poultry and dairy animals, and laundered clothing. Inside the main house they cleaned, cared for the Speed children, mended clothing, provided personal assistance to the family and their guests, and ensured that everyone had comfortable accommodations. The reputation for hospitality prized by southerners was possible only because of the labor provided by enslaved people.

Despite his first-hand observation of slavery, Lincoln’s writings never refer to the enslaved people he encountered at Farmington, nor comment on his personal opinion of what he saw during his only extended plantation experience.

Historian David H. Donald, in We Are Lincoln Men (Simon & Schuster, 2003), described the visit to the Speed plantation as “…one of the happiest times in Lincoln’s life.” Certainly, it was one of the most carefree times in his life. He had few responsibilities and, other than a bad tooth which a dentist failed to extract, few troubles. He met people who later became important to him politically, including Joshua’s oldest brother, James, who Lincoln visited regularly at his Louisville law office to read books and discuss politics.

The gregarious Lincoln also romped with Joshua’s sisters, admitting in his September 27, 1841 “Bread and Butter” (or thank-you for your hospitality) letter to Mary Speed that he locked her in a room to keep her from “committing an assault and battery upon me.” This letter shows the friendly, affectionate relationship that existed between Lincoln and his host’s sisters, nieces, and mother, Lucy Speed, who seemed to have taken a special interest in her son’s friend. As a token of affection, Mrs. Speed gave Lincoln an Oxford Bible. Years later, while serving as President, Lincoln sent an autographed photograph to Lucy Speed referencing her gift. Historians agree that Lincoln would not enjoy the same level of physical care he received at Farmington until he became President.

Lincoln helped Joshua woo and win his future wife, Fanny Henning. Fanny, an orphan who lived with her uncle, John Wil liamson, was not allowed to be alone with Speed. This situation was detrimental to their budding romance, so Lincoln distracted the older man in a political argument and Joshua proposed to Fanny. Although none of the parties involved ever confirmed the truth of this story, Lincoln later wrote to Speed that he believed, “God made me one of the instruments of bringing your Fanny and you together, which union I have no doubt He had fore-ordained.”

While Lincoln never refers specifically to slavery at Farmington, the September 1841 letter to Mary Speed included his earliest known written comments on the enslaved. When Lincoln and Joshua boarded the steamboat Lebanon for their voyage back to Springfield, they saw, on the boat, a dozen enslaved men headed for the south. Lincoln said of the encounter:

“They were chained six and six together. A small iron clevis was around the left wrist of each, and this fastened to the main chain by a shorter one at a convenient distance from the others; so that the negroes were Strung together precisely like so many fish upon a trot-line. In this condition they were being separated forever from the scenes of their childhood, their friends, their fathers and mothers, and brothers and sisters, and many of them, from their Wives and children, and going into perpetual slavery where the lash of the master is proverbially more ruthless and unrelenting than any other where [sic]; and yet amid all these distressing circumstances, as we would think them, they were the most cheerful and apparently [sic] happy creatures on board. One, whose offence for which he had been sold was an over-fondness for his wife, played the fiddle almost continualIy; and the others danced, sung, cracked jokes, and played various games of cards from day to day. How true it is that God tempers the wind to the shorn lamb, or in other words, that He renders the worst of human conditions tolerable, while He permits the best to be nothing better than tolerable.”

While Lincoln describes the scene in his letter to Mary rather dispassionately, he takes a far different tone several years later in a letter to Joshua Speed, when he says, “…that site [sic] was a continued torment to me.” Joshua later claimed that seeing the enslaved onboard that ship helped to focus Lincoln’s emancipationist sentiment.

Back in Springfield, Lincoln decided not to run for re-election to the State Assembly, and Speed settled his affairs in order to return to Louisville and marry Fanny Henning. Before leaving, however, a troubled Speed sought his friend’s advice over growing doubts that his love for Fanny was real. The day Speed left Springfield Lincoln tucked a letter into Speed’s pocket encouraging the romance. After the marriage was officiated, Lincoln gleefully claimed responsibility for the union and, inspired by the happy Speed marriage, mended his relationship with Mary Todd and married her.

Lincoln represented Speed’s legal interests in Illinois for several years while developing a prosperous legal career, first as Stephen Logan’s junior partner, then as senior partner with William Herndon. In 1846, the Illinois Whigs nominated and elected Lincoln to the U.S. House of Representatives.

Over the next several years, letters between the two men discussed business and politics, including the divisive topic of slavery. Their opinions diverged as Lincoln began to campaign against the extension of slavery into the Kansas and Nebraska territories, and Speed defended the constitutional right to own slaves.

Despite their opposing views over the most divisive topic of the time, the two men remained close friends. When Lincoln became the first Republican presidential candidate, Speed sent a congratulatory telegram and stressed that, although they were political opponents, he had no doubt Lincoln would be an honest president. Once elected, Joshua assured the new president that, “As a friend, I am rejoiced at your success—as a political opponent I am not disappointed.”

When Lincoln needed an Attorney General in 1864 he wanted a Kentuckian to fill the position. He first petitioned the Judge Advocate General, Joseph Holt. Holt refused the position but suggested Joshua Speed’s brother, James, who accepted the position.

After Lincoln’s assassination, James Speed, who witnessed the President’s death, wrote a letter to his mother, saying,

“The best and greatest man I ever knew, and one holding just now the highest and most responsible position on earth, has been taken from us, but do not be downcast and hopeless. This great Government was not bound up in the life of any one man. The great and true principles of self-government will under God be worked out by us or by better men.”

We may never fully understand the implications of Lincoln’s visit to Farmington or his friendship with Joshua Speed and his family. In the end, his closest friendship survived the tensions that brutally divided the nation. Years after Lincoln’s death, Joshua Speed declared of his friend:

“As President his acts stand before the world, and by them he will be judged; as a man, honest, true, upright and just, he lived and died.”

CONTACT FARMINGTON HISTORIC HOME

TOUR TIMES

Tuesday - Friday

10:30am 12:00pm 2pm

Saturday

11:00am 12:00pm 1pm

January

January 1st Closed New Years Day observance

January 6th-20th Closed for maintenance and planning

January 21-31st Tours may be scheduled by calling the office at (502) 452-9920

Rental Inquires and other requests may be directed to staff. The grounds will be open as usual.

We look forward to seeing you in 2025!

School & other group tours please contact the office to schedule.